Before

After

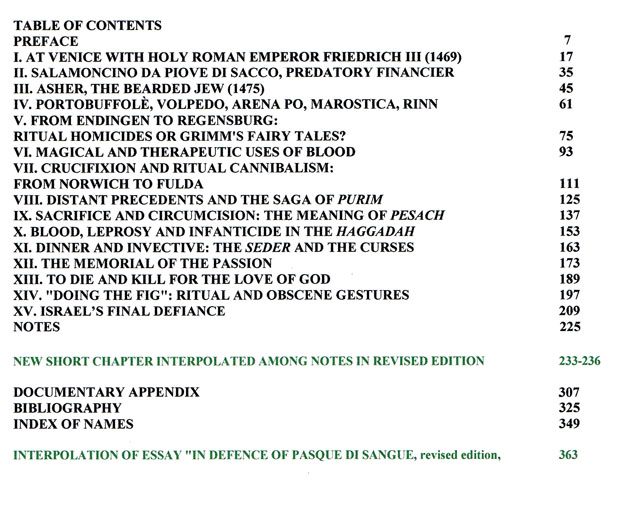

COMPARISON BETWEEN ORIGINAL AND REVISED EDITIONS OF BLOOD PASSOVER [Pasque di Sangue]

Before

After

The purpose of the present file is to provide a searchable version of BLOOD PASSOVER showing all major deletions and interpolations in both editions of the text. Most of the changes were made to the Preface, and Chapters Five, Six, Eleven, Twelve and Thirteen.

There are also a great many ritualistic disclaimers inserted under duress -- pressure exerted by the ADL, who had never even read the book.

These ritualistic disclaimers include the newly-invented fairy tale of the "voluntary donors", in which Toaff obviously does not believe, and for which there is no more evidence -- according to Toaff's own source material -- than for the existence of unicorns or the miracles of Mohammed.

The “evidence” consists of a single sentence from Ronnie Po-chia Hsia’s MYTH OF RITUAL MURDER, falsified, mistranslated and taken out of context, totally distorting the plain meaning of both context and sentence. This is the sort of thing that ruins the reputation of an historian.

It should not be forgotten that one of John Demianiuk's defenders in Israel was nearly blinded by an acid thrower while attending a funeral, while another one "committed suicide" by "falling" from a 15th story window.

Nevertheless, at the minor cost of mutilating a masterpiece, Toaff has achieved most of his aims: he got his book published, regaling us with even MORE disgusting examples of the eating, drinking and sucking of human blood by Jews, and nobody threw acid in his face.

Mea Culpa, or Eppur si Muove?

Red= deletions from first edition

Green = interpolations in revised edition

Blue = emphasis

For a short summary of these deletions and interpolations, click here

For added chapter of no interest to anyone, click here

For Ariel Toaff's Apologia pro Vita Sua, click here

For quotes from Ronie Po-chia Hsia, click here

For general discussion of Toaff's newly invented fairy tale of the "voluntary donors", click here

For excerpts from Mostri giudei ["Jewish Monsters"], click here

---

Minor errors in the 1st edition, mostly inconsistencies in the translation of proper names, have been corrected.

Since there are so many deletions and interpolations, the footnotes have been shuffled around a bit and appear in a different order in the revised edition, but are largely intact.

---

ARIEL TOAFF

BLOOD PASSOVER

EUROPEAN JEWS AND RITUAL MURDER

[back cover]

BLOOD PASSOVER

ARIEL TOAFF

Professor of Medieval and Renaissance History at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, Toaff has written Wine and Bread: A Jewish Community in

the Middle Ages (1989; translated into English under the title Love, Work and Death, and French under the title Le Marchand de Pérouse), Jewish Monsters: Jewish Myths and Legends from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era (1996) and Eating Jewish Style. Jewish Cooking in Italy from the Renaissance to the Modern Age (2000).

---

p. 7]

PREFACE

Ritual homicide trials are a difficult knot to unravel. Most researchers simply set out in search of more or less convincing confirmation of previously developed theories of which the researcher himself appears firmly convinced. The significance of any information failing to fit the preconceived picture is often minimized, and sometimes passed over entirely in silence. Oddly, in this type of research, that which is to be proven is simply taken for granted to begin with.

There is a clear perception that any other attitude would involve hazards and repercussions which are to be avoided at all costs.

There is no doubt that the uniformity of the defendant’s confessions, contradicted only by variants and incongruities generally relating to details of secondary importance, was assumed by the judges and so-called "public opinion" to constitute “proof” that the Jews, characterized by their great mobility and widespread dispersion, practiced horrible, murderous rituals in hatred of the Christian religion. The stereotype of ritual murder, like that of profanation of the Host and cannibal sacrifice, was present in their minds from the outset, suggesting to both judges and inquisitors alike the possibility of extorting symmetrical, harmonious and significant confessions, triggering a chain reaction of denunciations, veritable and proper manhunts and indiscriminate massacres.

While attempts have been made, in certain cases, to reconstruct the ideological mechanisms and underlying theological and mythological beliefs, with their theological and mythological justifications, which rendered the persecution of the Jews possible as the practitioners ofoutrageous and blood-thirsty rituals, particularly in the German-speaking countries of Europe, little or nothing has been done to investigate the beliefs of

p. 8]

the men and women accused -- or who accused themselves -- of ritual crucifixion, desecration of the host, haematophagy [eating of blood products] and cannibalism.

On the other hand -- if an exception be made for the first sensational case of ritual crucifixion, which occurred in Norwich, England, in 1146,or the equally well-known “blood libel” case at Trent, Italy, in 1475 -- the trial records and transcripts (usually referred to under the generic term “historical documentation”) constitute, in actual fact, very poor and often purely circumstantial evidence, highly condensed in form and very sparse in detail, totally insufficient for research purposes. Perhaps for this very same reason, that which is missing is often artificially added, assumed or formulated as a hypothesis, in the absence of any explicit probative evidence one way or another (i.e., in the desired direction); in the meantime, the entire matter is immersed in a tinted bath, from which the emerging image is superficial at best, enveloped in a cloud of mystery, with all the related paraphernalia from a distant past, and must remain forever incomprehensible to researchers intent on examining these problems through the application of anachronistic interpretive categories. These efforts -- obviously unreliable – are generally performed in good faith. Or, more exactly, almost always in good faith.

Thus, in Anglo-Saxon (British and American) historical-anthropological research on Jews and ritual murder (from Joshua Trachtenberg to Ronnie Po-Chia Hsia), magic and witchcraft traditionally feature among the favorite aspects under examination. This approach, for a variety of reasons, is enjoying an extraordinary rebirth at the present time (1). But that which seems to obtain a high degree of popularity at the moment is not necessarily convincing to meticulous scholars, not content with superficial and impressionistic responses.

Nearly all the studies on Jews and the so-called “blood libel” accusation to date have concentrated almost exclusively on persecutions and persecutors; on the ideologies and presumed motives of those same persecutors: their hatred of Jews; their political and/or religious cynicism; their xenophobic and racist rancor; their contempt for minorities. Little or no attention has been paid to the attitudes of the persecuted Jews themselves and their underlying patterns of ideological behavior – even when they confessed themselves guilty of the specific accusations brought against them. Even less attention has been paid to the behavioral patterns and attitudes of these same Jews; nor have these matters been considered worthy even of interest, attention or serious investigation. On the contrary: these behavioral patterns and attitudes have simply been incontrovertibly dismissed as non-existent -- as invented out of whole cloth by the sick minds of anti-Semites and fanatical, obtusely dogmatic Christians.

Nevertheless, although difficult to digest, these actions, once their authenticity is demonstrated or even supposed as possible,

p. 9]

should be the object of serious study by reputable scholars. The condemnation, or, alternatively, the aberrant justification of these rituals cannot be imposed upon researchers as the sole, and banal, options. Scholars must be permitted the possibility of attempting serious research on the actual, or presumed, religious, theological and historical motivations of the Jewish protagonists themselves. Blind excuses are just asworthless as blindly dogmatic condemnation: neither can demonstrate anything other than that which already existed in the mind of the observer to begin with. DELETED It is precisely the possibility of evading any clear, precise and unambiguous definition of the reality of ritual child murders rooted in religious faith which has facilitated the intentional or involuntary blindness of Christian and Jewish scholars alike, both pro- and anti-Jewish.

Any additional example of the two-dimensional “flattening” of Jewish history, viewed exclusively as the history of religious or political “anti-Semitism” at all times, must necessarily be regretted. When “one-way” questions presuppose “one-way” answers; when the stereotype of “anti-Semitism” hovers menacingly over any objective approach to the difficult problem of historical research in relation to Jews, any research ends up by losing a large part of its value.

All such research is thus transformed, by the very nature of things, into a “guided tour” conducted against a fictitious and unreal background, in a “virtual reality show” intended to produce the desired reaction, which has naturally been decided upon in advance (2). FOOTNOTE DELETED 2) For example, the recent volume by S. Buttaroni and S. Musial, Ritual Murder. Legend in European History, Crakow - Nuremberg - Frankfurt, 2003, opens with a preamble which is, in its way, conclusive: "It is important to state from the very beginning that Jewish ritual murder never took place. Today proving such theories wrong is not the goal of scientific research" (p. 12).

As stressed above, it is simply not permissible to ignore the mental attitudes of the Jews who were tried, tortured and executed for ritual murder, or persecuted on the same charge. At some point, we must ask ourselves whether the “confessions” of the defendants constitute exact records of actual events, or merely the reflection of beliefs forming part of a symbolic, mythical and magical context which must be reconstructed to be understood. In other words: do these “confessions” reflect merely the beliefs of Gentile judges, clergy and populace, with their private phobias and obsessions, or, on the contrary, of the defendants themselves? Untangling the knot is not an easy or pleasant task; but perhaps it is not entirely impossible.

In the first place, therefore, we must investigate the mental attitudes of the Jews themselves, in the tragic drama of ritual sacrifice, together with the accompanying religious beliefs and superstitious and magical elements. Due attention must be paid to the admissions which made ritual murder appear “plausible” within a particular historical and local context, identifiable within a succession of German-speaking territories on both sides of the Alps, throughout the long period from the First Crusade to the twilight of the Middle Ages. In substance, we should investigate the possible presence of

p. 10]

Jewish beliefs relating to ritual child murders, linked to the feast of Passover, while attempting to reconstitute the significance of any such beliefs. The trial records, particularly the minutely detailed reports relating to the death of Little Simon of Trent, cannot be dismissed on the assumption that all such records represent simply the specific deformation of beliefs held by the judges, who are alleged to have collected detailed but manipulated confessions by means of force and violence to ensure that all such confessions conformed to the anti-Jewish theories already in circulation at the time.

A careful reading of the trial records, in both form and substance, recall too many features of the conceptual realities, rituals, liturgical practices and mental attitudes typical of, and exclusive to, one distinct, particular Jewish world – features which can in no way be attributed to suggestion on the part of judges or prelates – to be ignored. Only a frank analysis of these elements can make any valid, new and original contribution to the reconstruction of beliefs relating to child sacrifice held by the alleged Jewish perpetrators themselves -- whether real or imagined – in addition to attitudes based on the unshakeable faith in their redemption and ultimate vengeance against the Gentiles, emerging from blood and suffering, which can only be understood in this context.

In this Jewish-Germanic world, in continual movement, profound currents of popular magic had, over time, distorted the basic framework of Jewish religious law, changing its forms and meanings. It is in these "mutations" in the Jewish tradition – which are, so to speak, authoritative – that the theological justifications of the commemoration [in mockery of the Passion of Christ] is to be sought, which, in addition to its celebration in the liturgical rite, was also intended to revive, in action, vengeance against a hated enemy continually reincarnated throughout the long history of Israel (the Pharaoh, Amalek, Edom, Haman, Jesus). Paradoxically, in this process, which is complex and anything but uniform, elements typical of Christian culture may be observed to rebound -- sometimes inverted, unconsciously but constantly -- within Jewish beliefs, mutating in turn, and assuming new forms and meanings. These beliefs, in the end, became symbolically abnormal, distorted by a Judaism profoundly permeated by the underlying elements and characteristic features of an adversarialand detested religion, unintentionally imposed by the same implacable Christian persecutor.

DELETED: We must therefore decide whether or not the alleged “confessions” relating to the crucifixion of children the evening before Passover; the testimonies relating to the utilization of Christian blood in the celebration of the feast of the Passover, represent, in actual fact, mere myths, i.e., beliefs and ideologies dating far back

p. 11]

in time; or actual ritual practices, i.e., events which actually occurred, in reality, and were actually celebrated, in prescribed and consolidated forms, with their more or less fixed baggage of formulae and anathemas, accompanying the magical practices and superstitions which formed an integral part of the mentality of the Jews themselves.

CHANGED In any case, I repeat, we should avoid the.. CHANGED, p. 13 of new edition: In any case, even in eliminating the calumnious stereotype of ritual child murder, central to the accusation, we should avoid the easy short-cut of considering these trials and testimonies only as projections -- extorted from the accused by torture and other coercive methods, both psychological and physical -- of the stereotypes, superstitions, fears and beliefs of the judges and populace. Such a method would trigger a process inevitably leading to the dismissal of these same testimonies as “valueless documents with little basis in reality”, except as “indications of the obsessions of a Christian society” which saw, in the Jew, merely a “distorted mirror image” of its own defects. This task appears to have seemed absolutely prohibitive to many scholars, even famous ones, well-educated men of good will, having concerned themselves with this difficult topic.

First, Gavin Lanmuir, who, starting from the facts of Norwich, England, considers the crucifixion and ritual haemotophagia, which appear in two different phases of history, as simply the cultivated and interested inventions of ecclesiastical groups, denying the Jews any role at all except a merely passive one, devoid of responsibility (3).

Lanmuir was later followed by Willehad Paul Eckert, Diego Qualiglioni, Wolfgang Treue and Ronnie Po-Chia Hsia, who, although examining the phenomenon of ritual child murder from different points of view, intelligently and competently, starting with the late MiddleAges, paying particular attention to the Trent trial documentation, considered it all tout court and often a priori a baseless libel, an expression of hostility on the part of the Christian majority against the Jewish minority (4).

According to the point of view adopted by these researchers, the inquisitor’s interrogation methods and tortures served no purpose other than to orchestrate a completely harmonious confession of guilt, i.e., of adherence to a truth already existing in the minds of the inquisitors. The use of leading questions and a variety of stratagems, including, in particular, refined torture, were intended to force the defendants to admit that the victim had indeed been kidnapped and tortured according to Jewish ritual, and finally killed in hatred of the Christian faith. The confessions are said to be obviously unbelievable, since the murders were allegedly committed to permit the ritual use of Christian blood, in violation of the Biblical prohibition against the ingestion

p. 12]

of blood, a prohibition scrupulously observed by all Jews. DELETED As to torture, it is best to recall that its use in the municipalities of northern Italy, at least from the beginning of the 13th century, was regulated, not only by tractate, but by statute as well. As an instrument for determining the truth, torture was permitted in the presence of serious and well-justified clues in cases in which it was considered truly necessary by the podestà [magistrate] and judges. All confessions extorted in this manner, to be considered valid, had to be corroborated by the inquisitor, later, under normal conditions, i.e., in the absence of physical pain or even the threat of renewed torture (5). These procedures, while unacceptable in our eyes today, were therefore in fact normal, and seem to have been observed in the case of the Trent trials.

FOOTNOTE 5 DELETED: In this regard, see E. Maffei's recent Dal reato alla sentenza. Il processo criminale in età communale, Rome, 2005, pp. 98-101.

Israel Yuval, following in the footsteps of Cecil Roth’s stimulating pioneering study (6), is more critical and seems more open-minded. Yuval stresses the link between the “blood libel” accusation and the phenomenon of the mass suicides and child murders during the German Jewish communities during the First Crusade. The picture which emerges is one of Ashkenazi Jewry’s hostile and virulent reaction against surrounding Christian society, a reaction finding expression, not only in liturgical invective, but above all, in the conviction that the Jews themselves were capable of compelling God to wreak bloody revenge against their Christian persecutors, thus bringing redemption closer(7). More recently, Yuval very relevantly demonstrated that the Ashkenazi responses to ritual murder accusations were surprisingly weak.

These responses, whenever they were recorded, contained not the slightest rejection of the probative evidence; rather, they consisted of a mere tu quoque of the accusation against Christians: "Nor are you, yourselves, exempt from guilt of ritual cannibalism" (8). As Yuval wrote, David Malkiel had already noted the manner in which phenomenal prominence was given to the scene, described in a secondary Midrasheven in the illustrations of the Passover Haggadah of the German Jewish communities, to the scene, of the Pharaoh taking a health-giving bath in the blood of cruelly massacred Jewish children (9). The message, which cast not the slightest doubt upon the magical, therapeutic effectiveness of children’s blood, seemed intended to turn the accusation around. “It is not we Jews, or, if you wish, not just we Jews, who have committed such actions; the enemies of Israel in history have been guilty of these things as well, in which case it was Jewish children who were the innocent victims”.

DELETED Any showing that these murders, celebrated in the Passover ritual, represented, not just myths, i.e., more or less consistently widespread, consistent religious beliefs,

p. 13]

but, rather, actual rites, pertaining to organized groups and forms of worship which were actually practiced, requires a respect for due methodological prudence. The existence of this phenomenon, once it is unequivocally proven, must be viewed within its historical, religious and social context, not to mention the geographical environment in which it is presumably said to have found expression, with all the related and peculiar characteristics which cannot be replicated elsewhere. In other words, we must attempt to search for the heterogenous elements and particular historical-religious experiences which are alleged to have made the killing of Christian children for ritualistic purposes appear plausible, during a certain period, within a certain geographical area (i.e., the German-speaking regions of trans-Alpine and Cisalpine Italy and Germany, or wherever there were strong ethnic elements of German Jewish origin, any time between the Middle Ages and the early modern era), as the expression of collective adjustment of Jewish groups and a presumed desire on the part of God in this sense, or as the irrational instrument of pressure to reinforce that desire [on the part of God], as well as in the mass suicides and child murders "for the love of God", during the First Crusade.

In this research, we should not be surprised to find customs and traditions linked to experiences which did not exist elsewhere: experiences which were to prove more deeply rooted than the standards of religious law itself, although diametrically opposed in practice, accompanied by all the appropriate and necessary formal and textual justifications. Action and reaction: instinctive, visceral, virulent, in which children, innocent and unaware, became the victims of God’s love and vengeance. The blood of children, bathing the altars of a God considered to be in need of guidance, sometimes, of impatient compulsion, impelling Him to protect and to punish.

At the same time, we must keep in mind that, in the German-speaking Jewish communities, the phenomenon, where it took root, was generally limited to groups in which popular tradition, which had, over time, distorted, evaded or replaced the ritual standards of Jewish halakhah, in addition to deeply-rooted customs saturated with magical and alchemical elements, all combined to form a deadly cocktail when mixed with violent and aggressive religious fundamentalism. There can be no doubt, it seems to me, that, that, once the tradition became widespread, the stereotypical image of Jewish ritual child murder continued inevitably to take its own course, out of pure momentum. Thus, the Jews were accused of every child murder, much more often wrongly than rightly, especially if discovered in the springtime. In this sense, Cardinal Lorenzo Ganganelli, later Pope Clement XIV,

p. 14]

was correct in his famous report, in both his justifications and his “distinctions” (10).

The records of the ritual murder trials should be examined with great care and with all due caution. In connection with the witchcraft trials, Carlo Ginzburg pointed out that the defendants (or victims), in a “show trial” of this type,

“…ended up by losing all sense of their own cultural identity, as a result of the acceptance, in whole or in part, by violence or apparently out of spontaneous free choice, of the hostile stereotype imposed by their persecutors [i.e., a sort of Medieval “Stockholm Effect”]. Anyone who fails to conform by simply repeating the results of these findings of historical violence must seek to work upon the rare cases in which the documentation is not just formally set forth in question and answer form; in which, therefore, one may find fragments relatively immune from distortions of the culture which the persecution was intent upon blotting out" (11).

The Trent trials are a priceless document of this very kind. The trial records -- especially, the cracks and rifts in the overall structure permitting the researcher to distinguish and differentiate, in substance, not just in form, between the information provided by the accused and the stereotypes imposed by the inquisitors are dazzlingly clear. This fact cannot be glossed over or distorted by means of preliminary categorizations of an ideological or polemical nature, intended to invalidate those very distinctions. In many cases, everything the defendants said was incomprehensible to the judges – often, because their speech was full of Hebraic ritual and liturgical formulae pronounced with a heavy German accent, unique to the German Jewish community, which not even Italian Jews could understand (12); in other cases, because their speech referred to mental concepts of an ideological nature totally alien to everything Christian. It is obvious that neither the formulae or the language can be dismissed as merely the astute fabrications and artificial suggestions of the judges in these trials. Dismissing them as worthless, as invented out of whole cloth, as the spontaneous fantasies of defendants terrorized by torture and projected to satisfy the demands of their inquisitors, cannot be imposed as the compulsory starting point, the prerequisite, for valid research, least of all for the present paper. Any conclusion, of any nature whatsoever, must be duly demonstrated after a strict evaluation and verification of all the underlying evidence sine ira et studio, using all available sources capable of confirming or invalidating that evidence in a persuasive and cogent manner.

p. 15]

DELETED The present paper could not have been written without the advice, criticism, meetings and discussions with Dani Nissim, a long-time friend, who, in addition to his great experience as a bibliographer and bibliophile, made available to me his profound knowledge of the history of the Jewish community of the Veneto region, and of Padua in particular. The conclusions of this work are nevertheless mine alone, and I have no doubt that that the above named persons would very largely disagree with them. I have engaged in lengthy discussions of the chapters on the Jews of Venice with Reiny Mueller, over the course of which I was given highly useful suggestions and priceless advice. Thanks are also due to the following persons for their assistance in the retrieval of the archival and literary documentation; for their encouragement and criticism, to Diego Quaglioni; Gian Maria Varanini; Rachele Scuro; Miriam Davide; Ellioth Horowitz; Judith Dishon; Boris Kotlerman and Ita Dreyfus.Grateful thanks are also due to those of my students who participated actively in my seminars on the topic, held at the Department of Jewish History at Bar-Ilan University (2001-2002 and 2005-2006), during which I presented the provisional results of my research. First and foremost, however, I wish to thank Ugo Berti, who persuaded me to undertake this difficult task, giving me the courage to overcome the many foreseeable obstacles which stood in the way.--

p. 16]

[Illustration]

[CAPTION OF MAP: RITUAL HOMICIDE ACCUSATIONS IN THE 15TH CENTURY]

p. 17]

CHAPTER ONE

AT VENICE WITH HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR FRIEDRICH III (1469)

It was in February of 1469 that Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich III, traveling from Rome, made his solemn entrance at Venice with a long retinue for which that which was to be his third and last official visit to the city which he so loved and admired (1). It was to be his first visit to the City of Venice since his triumphant reception immediately following his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope in Rome in1452 (2).

As was customary on these magnificent occasions, Friedrich spent entire days in diplomatic meetings and in receiving the official visits of ambassadors, and in conferring diplomas, stipends and privileges of all sorts upon beneficiaries selected from long lists of names prepared by his officials, as dictated by imperial interests and his own. In those days, intriguers, wheeler-dealers and adventurers attached to the monarch’s court, or who thought they were, toiled with a calculated industriousness to intercede in favor of various persons seeking official ratification of their own professional and economic success; of priests, patricians and academics bent upon crowning their own cursus honorum through the attainment of some precious imperial investment, or those of a variety of ethnic and religious communities intent on achieving confirmation of their ancient or recent privileges, not to mention merchants and intriguers intent on covering up affairs of dubious honesty and scraping up advantages for themselves during the solemn visit (3).

Friedrich was known as a fanatical and often naive collector of relics of all types. It is not therefore surprising that the objectives of his trip to Venice should have included a passionate and unrestrained hunt for relics, hawked about in abundance by wheeler-dealers and impertinent intermediaries at high prices, a fact noted with malicious humor by Michele Colli, a salt superintendent, in a report sent from Venice to the Duke of Milan, in which he cast doubt on Friedrich's alleged competence

p. 18]

where relics were concerned. According to the Milanese official, the Emperor, in this type of business, which he presumed to carry out directly and without regard to price, was a sucker to be plucked assiduously, adding, to add to the ridicule, half-seriously half facetiously, that "certain Greeks sold him dead bones including the tail of the ass that brought Christ to Bethlehem" (4).

On this occasion, some supposed relics of Saint Vigilius found their way to Venice in the hands of a loving and faithful subject of Friedrich, Giovanni Hinderbach, a famous humanist and man of the Church who had traveled from Trent to the City of the Lagoons, not only to present the Emperor with the highly-valued relics, but above all as an act of gratitude, on the occasion of his receipt of his much sought-after investiture of the temporality of the episcopate of Trent. Again, it was Colli who informed the Duke of Milan that "His Illustrious Majesty invested the Bishop of Trent with a thousand temporal solemnities and celebrations" (5). But Hinderbach was not the only person to have undertaken the uncomfortable journey from Trent to Venice during the German Emperor’s distinguished presence in the city.

Tobias da Magdeburg was an obscure Jewish herb alchemist who, after traveling down from his native Saxony and finding exile among the mountains of the region of Trent, practiced the art of medicine and surgery with some success, at least on the local market. A few years later, he was to meet Hinderbach under much unhappier circumstances, under indictment for participation in the cruel ritual murder of Little Simon, later sainted as Simon of Trent. Imprisoned in the castle of Buon Consiglio and admitting his guilt, he was to meet a cruel death at the stake, accompanied by the confiscation of all his goods (6).

Maestro Tobias appears to have been acting in accordance with other motives during the Emperor’s official visit to Venice, particularly, the possibility of meeting large groups of German Jews arriving from the other side of the Alps along with Friedrich’s baggage train, many of whom Tobias looked forward to seeing again after years of involuntary separation. There was no shortage of German Jews at Venice in February of 1469: disciplined, humble, but totally self-absorbed and self-interested.

In his depositions before the judge of Trent in 1475,Tobias was not exaggerating when, after recalling his own presence in the city during "His Most Serene Highness’s visit to Venice”, he stressed that many Jewish merchants, in crossing the Alpine barrier, had actually traveled from the German territories to the City of the Lagoons for the purpose of acquiring a wide variety of high-priced goods without paying taxes or duty of any kind, passing them off

p. 19]

as goods owned by the Emperor, in whose baggage train they were said to have found their way back to Germany. This astute and bold stratagem was well worth the physical and economic cost of the difficult trip to the city of the Doges (7).

But Tobias’s presence in Venice was not due to any mere nostalgia for the people among whom he had been born and grew up. As a physician, and as a Jewish physician in particular, he knew that the Emperor, during his visit, would, as he was normally accustomed to do, grant doctoral degrees in medicine to a swarm of more or less highly recommended candidates, including a few Jews. In fact, it was during that same February of 1469 that Friedrich granted a license permitting the College of Physicians of San Luca, an institution of higher learning teaching students of various origins -- not just Venetians -- to confer the insignia of Imperial Authority upon eight medical degrees per year (8). Enea Silvio Piccolomini, later Pope Pius II, recalled the manner in which Friedrich graduated a swarm of medical students during his second visit to Italy.

The number of Jews on the Emperor’s lists of candidates remains unknown. Nor do we know who filed the petitions to inscribe these Jewish candidates, or the methods used, or the reasons for doing so. We only know that many Jewish physicians, of various origins, in addition to Tobias, a resident of Trent, were in Venice during the Emperor’s visit, attracted by an opportunity of obtaining some much sought-after title from Emperor Friedrich in person; nor do we know how many of them had already spent considerable periods of time in the City of the Lagoons in search of fame and fortune (9). Among them were the Jews Moschè Rapp, Lazzaro (10) and the better-known Omobono (Simcha Bunem or Bunim), keeper of the pharmacy "della Vecchia" at San Cassian, with a house at San Stae, only a few steps from the Albergo dei Bresciani ("magister Homobon, Jewish physician, at the Speziaria de la Vechia at San Cassian, with his house near San Stae, not far from theCasa de Bressani, at Venice") (11). Accompanying them was the physician Moisè da Rodi, whose presence is attested to with certainty in1473 (12), but who probably arrived in Venice even earlier, and "Maestro Theodoro (Todros), Jewish physician", who reached Venice in1469 with Friedrich (13).

The best-known of all, however, was, without doubt, the rabbi and barber surgeon Jehudah messer Leon, certainly a product of Ashkenazi Jewish environment, if his origins at Montecchio in the Vicentino region are indeed a fact (14). This same Leon, who resided in Venice starting in 1469 at the earliest, where his son David was born, was officially granted his degree in medicine

p. 20]

during the Emperor’s visit, although formally the diploma was only signed a few days later by the imperial notary at Pordenone (but still in the month of February) (15). Similarly, years later, in August of 1489, the Emperor, still at Pordenone, is said to have granted a doctorate in medicine to two Jewish candidates, both of them from Sicily and belonging to the Azeni family at Palermo, David di Aronne and Salomonedi Mosè (16).

The petitions of the Jews to the Emperor, who had always been highly esteemed for his benevolent attitude, filed during his stay in Venice during the winter of 1469, were submitted by an ambassador admitted to Friedrich’s presence for that particular occasion. The occasion was described as follows, early in the 16th Century, with some satisfaction although with undoubted exaggeration, by the chronicler Elia Capsalia, rabbi of Candia, who had studied medicine at the Talmudic academy of Padua:

"The Emperor (Friedrich III) was very favorable to the Jews. During his visit to Venice (in 1469), when his vassals and subjects presented him with (gastronomic) gifts, he never refused to eat them before his servants and functionaries had tasted them first, as is the custom among emperors. Whenever the Jews brought him gifts of this kind, Friedrich never hesitated to eat any of the dishes immediately, saying that he had complete faith in the loyalty and honesty of his Jewish subjects.

"Later, Frederic, traveling from Venice, went to Padua to gain an impression of that city. On that occasion, the Serenissima prepared a carriage for him and placed it on the city walls: the horses pulled the carriage from which the Emperor admired the entire city. This was doneso that he might easily verify the thickness and solidity of the walls (of Padua). Friedrich signed a pact with Venice and remained its faithfully for the entire time he lived" (17).

In all probability, the ambassadorship of the Jews conferring with Friedrich III as described by Capsali was headed by David Mavrogonato (in Italian, Maurogonato), an adventurer and not overly-scrupulous businessman in the service of the Republic of Venice, a person of enormous financial resources and great influence, a native of Candia who was often sent on hazardous missions to the lands of the Aegean and the Great Turk, where he was to run many risks and die a cruel death; on the other hand, he was certainly capable of procuring sumptuous stipends and profitable privileges for himself (18).

p. 21]

Maestro Tobias da Magdeburg, the humble physician from Trent, had seen Mavrogonato at Venice during the days of the imperial visit, although he did not know Mavrogonato’s name. He had observed Mavrogonato with respect and reverential fear; he knew approximately where he lived, although he did not know the exact address; but he was well aware that he would never have been able to approach Mavrogonato without undergoing the suspicious appraisal of Mavrogonato’s bodyguards. Perhaps Tobias thought that Mavrogonato’s recommendation would help get him, Tobias, included in the list of people enjoying the Emperor's favor, or those about to receive a Doctorate, but he was unable, or did not dare, to ask for it. The personage and appearance of Mavrogonato nevertheless remained imprinted in his memory after many years; in 1475, in speaking to the judges at Trent, he envisioned Mavrogonato as follows, erroneously imagining that he might be still alive:

"He might have been forty four or forty five years old; he wore his hair long and wore a black beard, like the Greeks. He wore a black cloak that came down to his feet, and covered his head with a black cap. In substance, he dressed like the Greeks" (19).

But who was David Mavrogonato really? An ambiguous and mysterious character, Mavrogonato appeared in Venice in 1461 on his own initiative to reveal a conspiracy being hatched on the island of Candia against the Serenissima. The Council of Ten did not hesitate to take the Jewish merchant into its service and send him back to Candia on a secret mission to spy on the conspirators and report them to the Venetian authorities, after gathering the evidence required for their arrest (20). Mavrogonato carried out the mission to perfection, although his tireless commitment finally ended by blowing his cover, rendering continued residence on his native island impossible, since, as he claimed, both Greeks and Jews "pointed him out with their fingers", considering him a vile informer, or malshin in Jewish juridical terminology, a term with lethal penal implications (21). We also know that Mose Capsali, rabbi at Constantinople, had threatened Mavrogonato with excommunication at the request of the Jews of Candia (22).

The privileges requested early in his career by Mavrogonato in return for services rendered were granted without delay and with expressions of profound gratitude by the Council of Ten in December of 1463. These rights, which extended to his sons Jacob and Elia and his descendents in perpetuity included, among other things, exemption from the wearing of the distinctive sign required of the Jews, and authorization

p. 22]

to move about armed wherever he wished. He was not, however, granted the privilege, odd in appearance, but perfectly consistent with the type of persons with whom he had to deal, of striking two names off the list of banned wanted by the Serenissima for the crime of homicide (23). Mavrogonato, Judeus de Creta et mercator in Venetiis, knew full well who might have benefited from such a clause, and had very definite ideas about certain people condemned in absentia who might thus have been permitted to return in the territories under Venetian domination. At this point, the entrepreneurial Jew from Candia, a permanent resident of Venice since the beginning of 1464, traveling frequently and easily, supervising his goods and entering and leaving the port en route for Candia and Constantinople, was officially a spy in the service of the Republic and at its disposal for other, more or less hazardous, secret missions.

In effect, Mavrogonato is thought to have been sent to Candia and Constantinople at least four times, in 1465, the next year, in 1468 and in1470, during the first Venetian-Turkish War (24). It is possible that, in 1468, on the eve of Friedrich’s imperial visit to Venice, Mavrogonato may have accompanied a vessel, loaded with goods owned by himself, from Candia to the Venetian landing place. In June of 1465, a decree signed by the Council of Ten officially admitted that Mavrogonato had been sent to the capital of the Great Turk to spy on the enemy; in1466, he was referred to the "Jew from Crete, called David", called upon by Venice to participate in the peace negotiations with the Sultan Mahomet II (25).

David Mavrogonato died as mysteriously as he had lived, probably during his fourth mission. On 18 December 1470, the Doge of Venice, writing to the Duke of Crete, mentioned the death of his secret agent, but without providing any details as to the circumstances of his death (26). Mavrogonato may have accepted the dangerous assignment of plotting the Great Turk’s assassination in one way or another, and may for some reason have failed in the mission, meeting an unexpected death in the process. Other, later, clues are also thought to point in this direction.

Among the requests filed by Mavrogonato with the Council of Ten after his first secret mission to Candia in the years 1461-1462, was that of being permitted to avail himself of a body guard, assigned to his personal defense ("that you might deign to grant him the privilege [...] of keeping [...] some person near him for the safety of his person, so that no violence or ignominy may be done to him by some villain or other evil person").

p. 23]

Once his petition had been accepted by the Venetian legal authorities in February 1464, the merchant from Candia made haste to appoint a person originally described as a sort of bodyguard, but referred to in the document as Mavrogonato’s "associate", a designation quite distinction scope as well as quality. This bodyguard, or “associate”, was to share in almost all the privileges granted by the city of Venice to Mavrogonato, including that of being authorized to engage in business of any kind, on a basis of equality with Venetian merchants, and being permitted to move about the city and territory wearing the black hat of a Christian gentlemen instead of the crocus-colored beret of the Jews(for this reason, Mavrogonato, in Venice and its domains, was known as "Maurobareti") (27). Mavrogonato was an experienced and rich businessman, but not a muscular street fighter or expert in the martial arts; these latter services were to be provided by a man bearing the name of Salomone da Piove di Sacco, known throughout Venice and the entire Veneto region as a banker, merchant and rough-and-ready financier, as bold as he was unscrupulous (28). Starting in 1464 and continuing thereafter, Mavrogonato is thought to have entrusted his affairs to Salomone da Piove di Sacco during his enforced and prolonged absences from Venice, including the management of his lordly dwelling at San Cassian and his joint interest in commercial ventures undertaken on the maritime routes to the great markets of the Levant.

Finally, Mavrogonato is also believed to have entrusted Salomone da Piove with some of his own precious secrets as a diplomatic spy in the pay of Venice. On the eve of his first, risky trip to Constantinople in June 1465, David Mavrogonato informed the Council of Ten that he had indeed confirmed Salomone as his business agent at Venice "due to the complete faith which I have in him" (29).

Salomone’s ancestors had arrived in Italy in the last part of the 14th century from the Rhine region in Germany, perhaps from the same important seat of the archbishop of Cologne. The family had gradually extended its offshoots from Cividale del Friuli, where Maruccio (Mordekhai) and Fays -- Salamone’s father and grandfather respectively -- had operated in the local money market, to Padua, where, in the mid-15th century, the same Salomone managed the bank of San Lorenzo in the city district of the same name (30).

Salomone and his clan formed part of a migratory flow extending to all regions of northern Italy since the very late 14th century, involving the massive transalpine migration of entire German-speaking communities, both Christians and Jews,

p. 24]

from the Rhineland, Bavaria and upper and lower Austria, Franconia and Alsace, the Kärnten, Styria and Thüringen, Slovenia, Bohemia and Moravia, Silesia, Swabia and Saxony, Westphalia, Württemburg in the Palatinate, Brandenburg, Baden, Worms, Regensburg and Spira. A heterogenous German-speaking population, made up of rich and poor, entrepreneurs and artisans, financiers and scoundrels, men of religion, adventurers and rascals, traveling from the transalpine territories via the mountain crossings in a process of long duration, towards the lagoons of Venice, as well as the cities and lesser centers of the terra firma of the Veneto region (31).

This was a large-scale phenomenon containing a large Jewish component which had already come to the fore in the regions of northern Italy, in consequence of the persecutions following the Black Death in the mid-14th century as well as sporadically during the century before.

Ashkenazi, i.e., German, Jewish communities of diverse numerical consistency formed in a myriad of localities, large and small, from Paviato Cremona, from Bassano to Treviso, from Cividale to Gorizia and Trieste, from Udine and Pordenone to Conegliano, from Feltre andVicenza to Rovigo, from Lendinara to Badia Polesine, from Padua and Verona to Mestre (32). Here they stayed, a stone’s throw from Venice, an enterprising Jewish community of considerable economic weight, whose members came mostly from Nuremberg and the adjacent areas. In 1382, a few Jews from Mestre obtained authorization to move to Venice to practice money-lending, but were expelled a few years later, in 1397, for failing to comply with the conditions under which the government of Venice had admitted them to the city (33).

The Serenissima thus returned to its traditional policy of refusing to grant permanent residence to Jews on the banks of the Great Canal, except under exceptional circumstances and for periods of short duration. This policy, frequently quite contrary to actual practice, witnessed Jews crowding the streets of certain city districts during the day and remaining there in great numbers even after dark, lodged in houses and inns, sometimes for long periods of time. There was no shortage of Jews in Venice: mostly physicians, influential merchants and bankers, having established themselves more or less permanently at Venice. The numerical consistency of this community, heterogenous in professions but more or less homogenous in ethnic origin, originating from the transalpine German-speaking territories, has, until today, been considered

p. 25]

from an unjustly simplistic point of view. Beginning in the second half of the 15th century, they tended to gather in one particular strategic area, a sheltered location in the international market at Rialto, the node of the great trading systems linking the city of Venice, by land and sea, to the centers of the plains of the Po River valley and the German-speaking regions which constituted a constant point of economic, social and religious reference, towards which the eyes of these Ashkenazi Jews continued to be directed (34). These areas included the districts of San Cassian, where a kosher butcher's shop soon opened, preparing meat according to the Jewish custom, Sant Agostino, San Polo and Santa Maria Mater Domini. At San Polo, they probably also attended the German-rite synagogue, authorized by the Venetian government in 1464 to serve "the Jews who reside in the capital or who meet there to carry on their businesses", with a decree which nevertheless limited their liturgical collective meetings to the participation of ten adults of the male sex (35).

Moreover, the Jewish community at Venice, like the others of more or less distant Ashkenazi origin to be seen in the more immediate and smaller centers of northern Italy, formed part of a German-Jewish koinè, consisting of German-speaking Jews on both sides of the Alps, linked by liturgical usages and similar customs, sharing the same history, often marked by events both tragic and invariably mythologized, as well as by the same attitude of harsh hostility to the arrogant Christianity of surrounding society, the same religious texts of reference, the same rabbinical hierarchies, produced by the Ashkenazi Talmudic academies to whose authority they intended to submit, and the same family structures (36). These communities made up a homogenous entity from the social and religious point of view, which might be called supranational, in which the Jews of Pavia identified themselves with those from Regensburg, the Jews from Treviso with the Jews of Nuremberg, and the Jews of Trent with those from Cologne and Prague, but certainly not with those from Rome, Florence, or Bologna.

Relations with the Italian Jews who often lived alongside them, where such relations existed, were markedly fortuitous, based on contingent common needs of an economic nature, and the common perception of being viewed as identical by the surrounding Christian environment.

Many of these Ashkenazi Jews did not speak Italian, and if or when they did speak it, it was difficult to understand them due to the heavy German inflection of their pronunciation and the many Germanic and Yiddish terms with which their phrases were cram-packed. Not only the Hebrew language,

p. 26]

but the common liturgical usage of German and Italian Jews, was pronounced in a radically different way, so that the two groups considered it impossible to pray together (37). It is not therefore surprising that Italian Jews were not on terms of much familiarity with German Jews.

Despite their close proximity, they had little knowledge of them, distrusted their aggressive economic audacity, which generally had little respect for the nation’s laws, and dissented from their religious orthodoxy, which they considered exaggerated and depressing. Sometimes, rightly or wrongly, they feared them.

The Italian Jewish koinè, i.e, of distant Roman origin (Jews active in the money trade only moved from Rome to seek permanent residence in the municipalities of central and northern Italy starting in the second half of the 13th century), lived side with the German Jewish koinè, of more recent origin, but without assimilating, without merging and without being influenced, except to a minor and quite secondary degree. They were distant brothers, even if they were not "brothers who hate and fear each other".

The first group of "Roman" Jews, i.e., Jews of Italian origin, flowing into the centers of the plane of the Po from their preceding seats in the Patrimonio of San Pietro, in Umbria, in the Marca d'Ancona, in the Lazio and in Campagna to carry on the authorized money trade, i.e., regulated by permits, did not reach these regions simultaneously with the arrival in those regions of the German transalpine Jews, active in the same profession. They in fact preceded them by several decades. The first Jewish money lenders at Padua and Lonigo, in the Vicentino region, were Italians, and initially settled there between 1360 and 1370. Jews of German origin only reached the region in consistent numbers at a later time, at the end of the century, and, in particular, at the beginning of the 15th century (38). A comparison of the clauses of the permits granted to the German Jews compared to those granted to the Italian Jews, often active in the same areas, reveals obvious traces of profound differences in religious usage and mentalities, sediments of particular and diverse historical experiences. The attitudes and ceremonial components, the fears and mistrust, the sense and dimension of life, the relations with the surrounding Christian society of these German Jews, immersed in the new Italian reality in which they felt profoundly foreign, remained influenced and marked by their experiences in the Germanic world from which they originated, and which they had only left physically.

The principal concern of these immigrants seemed to be, understandably, that of ensuring their physical safety

p. 27]

and the protection of their property against the dangers represented by a surrounding society which considered them treacherous and potentially hostile. Almost obsessively, the chapters of the permits repeatedly mention the exemplary punishments to be threatened to anyone causing damaging or injury to the Jews, or subjecting them to trouble or vexations.

The permit granted by the municipality of Venzone to the money lender Benedetto of Regensburg in 1444 contained the condition that wet nurses and Christian personnel in the service of the Jews were not to be molested or offended, nor could they be made to work on Sunday or the feast days of the Christian calendars (39). The transalpine Jews were particularly sensitive to the possibility of being falsely accused and, in consequence, of suffering from legal proceedings and expropriations, as shown by their preceding experience in the German territories, the scars of which they still bore. In 1414,Salomone da Nuremberg and his companions requested and obtained a concession from the government of Trieste stating that, if Jews accused of any crime or offense before the judges of that city would not be subjected to torture to extort confessions without at least four citizen witnesses, trustworthy and of good reputation, against them (40).The permits signed by the municipalities of Lombardy and Triveneto with the Ashkenazi Jews were characterized by a constant concern that they be guaranteed the freedom to observe their religious ritual and ceremonial standards with zealous scrupulousness.

The religious clauses inserted in the chapters were more detailed in this sense than those found in the contemporary permits granted to Jewish money lenders of Italian origin, undoubtedly an indication of greater adherence to the observation of religious precepts on the part of the Ashkenazi community than the Italian one. It was significant in this regard that the appearance of the clause relating to the undisturbed provision of kosher meat, i.e., meat butchered according to ritual law, appears for the first time in the permits granted to German Jews at the end of the14th century (from Pavia in 1387 to Udine in 1389, from Pordenone in 1399 to Treviso in 1401), approximately twenty years before this made its initial appearance, certainly in imitation of, and under the influenced by, the Ashkenazi prototype, in the permits of the Italian Jews(41).The religious clauses inserted in the permits of the German Jews include, in addition to the right to supply themselves with kosher meat to observe their festivities freely, the right not to be compelled to violate the standards of Hebraic law in the exercise of

p. 28]

their lending activities or having to appear in court on Saturday or the feast days of the Hebraic calendar. The same clauses furthermore permitted the safeguarding of the other Jewish alimentary norms, such as the supervised preparation of the wine, cheeses and bread (a clause usually missing from the permits granted to Italian Jews); the right to "attend synagogue" (Pavia 1387); to use a piece of land as a cemetery and to permit Jewish women to take regular baths of purification, after the end of their menstrual periods, in the city baths on particular days set aside for them (Pordenone, 1452) (42).

But the most characteristic clause, absolutely generalized in the permits of Jews of German origin, but significantly absent from the permits of the Italian Jews, was that referring to protection against forced conversions to Christianity. In particular, the Ashkenazi appeared obsessed with the possibility that their children might be kidnapped, subjected to violence or swindled with snares and tricks to drag them to the baptismal font. That this possibility was anything but remote seemed obvious to anyone having experienced this type of traumatic experience at first hand on the banks of the Rhine or the Main. Permits issued in Friulia, Lombardy and Veneto granted to German money lenders, as early as the end of the 14th century, explicitly prohibited friars and priests of any order from proselytizing among Jewish children not yet having reached their 13th birthday (43). In 1403, Ulrich III, bishop of Bressanone, granted the Jews of the Tyrol protection from any possible ecclesiastical claims to a right of forced conversion of Jewish children. This protection could, and did, include the dangers represented by baptized Jews, zealous and implacable in plotting the ruin of the Jewish communities from which they originated (44). In 1395, Mina da Aydelbach, representing the Jewish families of German origin residing in Gemona, first stopping place on the main road to the lagoons of Venice after the mountain crossing of Tarvisio, obtained, in the initial clauses of their permits explicitly provided for the immediate removal from the city of so-called "Jews turned Christian", who were said to constitute elements of scandal and disturbance (45).

The die was already cast between the Italian and German Jews, settled in the lands beyond the River Po, by the mid-15th century. With a few exceptions, the piazza was henceforth solidly in the hands of Yiddish-speaking Jews who, in the best of cases, badly mangled Italian (46). Informer times, they had crossed the Alps fearfully and almost on tip-toe, in search of sufficiently modest and desirable dwellings

p. 29]

so as to live and survive comfortably, but they also, when need arose, proved themselves enterprising in financial matters, courageous and even bold in their commercial undertakings, nonchalant and often arrogant and impudent in their relations with the government, only obeying the law when it was strictly necessary or too dangerous to do otherwise. Victory was now theirs, and it was because of these same banker sand merchants that many of them had been able to accumulate huge sums of capital in a relatively short lapse of time, such as to bear no comparison with the fortunes possessed by Christian mercantile families and patricians who were both more distinguished and of higher rank.

The chronology is relatively precise. In 1455, all Italian Jews active in the money trade were expelled from Padua and compelled to shutdown their banks, while the "Teutonic" Jews, divided from, and now entirely separate from, the Italian Jews, gained the upper hand in the local money market [Padua], the most important in the terra firma of the Veneto region, as early as ten years before. At Verona, all lending banks owned by Italian Jews had already been closed in 1447, while, in 1445, the permits of the Jewish bankers of Vicenza were not renewed(47). With the Italian Jewish banks shut down in all the principal centers of the Veneto region, a few district lending banks, few in number but of great economic potential, particularly because of the higher interest rates charged by them in comparison to the rates formerly charged by banks controlled Italian Jews, remained open to serve the needs of the clientele in the cities and in the countryside (48). These were the banks of Soave and Villafranca in the district of Verona, Mestre for Venice, and Este, Composampiero and, above all, Piove di Sacco in thePadua district (49).

The forced and almost simultaneous dismantling of the Jewish banks of Padua, Verona and Vicenza led, as an immediate consequence, to the almost total extinction of the Hebraic community of Roman origin, which was compelled, for the most part, to flow into the centers on the nearer side of the Po; on the other hand, however, it allowed other money lenders, from Treviso and the territories of Friulia, who took over the assets and management of the few remaining lending banks, to make extraordinary fortunes. As we have seen, these banks benefited from an extremely broad catchment area and could rely on a numerous and heterogenous clientele. Their economic success was therefore guaranteed and proved to be exceptional in scope. The lucky few bankers remaining on the piazza were almost all Ashkenazi, the same Jews who had hastened or more or less directly procured the financial ruin of the Italian Jews. The

p. 30]

most prominent among them was, in the end, Salomone di Marcuccio, owner of the Banco di Piove di Sacco and, after 1464, David Mavrogno da Candia’s official business associate, with a more or less official residence at Venice (50).

Rich and influential, Salomone, although not a man of great culture, was not averse to sponsorship ventures, in which field he established himself with flare and good taste. At Piove, where the local community was practically one of his fiefdoms, in 1465, he became associated with the German printer Meshullam Cusi, whose presence at Padua is attested to in the same year. Cusi undertook the initial printing of one of the first Hebraic cunabulae, certainly one of the most important and monumental, at Piove, towards the end of 1473. This was a classic ritualistic code, Arba'a Turim, a work of the German rabbi Ya'akov b. Asher (1270 circa 1340), whose family originated from Cologne but had carried on its activities for the most part at Barcelona in Catalunya, and later at Toledo in Castille.

The four volumes, printed on Cusi’s presses with great care and heedless of cost, were completed in July 1475 and constituted one of the most splendid and elegant examples of Hebraic printing (51).Certain copies of great beauty were printed on parchment and intended for a highly sophisticated readership, particularly from the economic point of view, one of the most important of whom was to be Salomone di Piove. The printing costs linked to the supplies of machinery, type, materials and labor, were to fluctuate between seven hundred and one thousand ducats, a large sum which Cusi might not have had available, without the direct or indirect joint involvement of the Jewish banker di Piove.

We believe that consideration should be given to the possibility that Salmone may have also undertaken another artistic-literary undertaking of great importance, at proportional economic cost. The precious miniatures of the so-called "Rothschild Miscellanea", one of the most sumptuous and famous of all Jewish legal codes, were executed in the decade between 1470 and 1480, probably in Leonardo Bellini’s workshop at Venice. The artistic decoration of the manuscript cost almost one thousand ducats, a sum equivalent to half the taxes paid by the entire Jewish community of the Duchy of Milan during the same period (52). Salomone may well have been the only Jewish sponsor living more or less permanently in the city of the lagoons able to make

p. 31]

an investment of such magnitude without difficulty. For purposes of comparison, we know that in 1473, Salomone, still active on the piazza of Venice, together with one of his sons, Marcuccio, his first born, was able to pay a gigantic sum, equal to 300 ducats in cash and another360 in credits, intended for the restoration of the perimeter wall of the old Arsenal (53).

Between 1468 and 1469, in view of Emperor Friedrich’s forthcoming visit to Venice, Salomone hosted a plenary meeting at Piove of the German rabbis of the Jewish community of northern Italy, presided over by their most authoritative exponent, the jurist Yoseph Colon, then active in the community of Mestre (54). The petitions said to have been presented by the Jewish ambassadorship to the solemn and magnificent Emperor during the anticipated audience described by Rabbi Elia Capsali di Candia in his chronicles may have been drawn upon that occasion.

During the summer of 1470, David Mavrogonato set sail from Venice to return to Candia for what was to be his last mission. He had long since prudently avoided reappearing on his native island. He was probably accompanied on this voyage by Salomone di Piove himself, who, at the end of June, left his son Salamoncino with a power of attorney for the purpose of collecting a huge loan from the bank Soranzo at Venice, a transaction which he would normally have conducted directly (55). As we know, this was a voyage from which Mavrogonato is thought never to have returned alive, meeting with his tragic demise a few weeks later, certainly before September of that year. From that time onwards, Mavrogonato’s name and memory were to be systematically omitted from all documents signed by his former associate, Salomone da Piove, as well as by Salamone’s sons, although reference to the privileges obtained by the influential merchant from Candia appears to have become an established custom. This is not surprising and cannot be merely accidental. Salomone certainly knew the truth about that last voyage to Constantinople in which Mavrogonato is believed to have met with unexpected death. Did Salamone know too much? Did he wish to forget, or rather, cause others to forget, that he had been with him on that tragic maritime voyage? What is certain is that Salomone da Piove was close to David Mavrogonato until the end. Perhaps too close.

It is not therefore surprising to learn that, at around this same time, Salomone personally took over a bold project, perhaps planned beforehand by his associate and collaborator from Candia,

p. 32]

"to take the life of the Great Turk", thus doing the government of Venice a great favor (56). To provide for the assassination of Mahomet II, the nonchalant financier informed the Council of Ten that he had sent a Jewish doctor named Valco, whose Italian name was probably derived from the well-known family of doctors, natives of Worms, called Wallach, Wallich or Welbush, to Constantinople, at his expense (57).

"Salamon, as appears in the books of Your Majesties the Council of Ten, due to his wish to do a great yourselves and all of Christianity agreat service by attempting to take the life of the Great Turk, chose, at his expense, sent for a Maestro Valco, a Jewish doctor, whom he sent with his own money" (58).

Even before that, we know that the Venetian authorities had been glad to avail themselves of the services of a Jewish barber-surgeon, Jacob da Gaeta, the Sultan’s personal physician, an expert spy and double agent, greedy for gain and treacherous, with whom Mavrogonato had maintained frequent contacts (59). It also appears that Maestro Jacob had reached Venice in secrecy, together with Gaeta, on the same vessel from Ragusa, in very late 1468, on the eve of the imperial visit and the Venetian congress of Jewish physicians, held on that occasion (60).

Maestro Valco, paid by Salomone, moved to Constantinople, and went quickly to work, but apparently with little result. Mahomet II was still alive and kicking when the Jewish banker from Piove finally died, between the end of 1475 and the very early part of the following year. But Salamone was occupied with certain other matters, much more serious and more disagreeable then merely "taking the life of the Great Turk" during that period, which was to prove fraught with danger for all the Jewish communities of northern Italy. The Trent trials of the Jews accused of little Simon’s martyrdom had ended with the condemnation and execution of the principal defendants, who were burnt at the stake or decapitated in June of 1475. Other defendants, including the women of the small community, were waiting to learn their final fate, after which the trial proceedings were suspended in April by order of Sigismundo IV, Count of Tyrol, and were then newly interrupted the following July by order of Pope Sixtus IV after a brief recommencement, requested by several parties for purposes of intervening in the affair. The Pope then personally sent a special commissioner to Trent, the Dominican, Battista de’ Giudici, bishop of Ventimiglia, with the task of investigating and

p. 33]

reporting on the facts. De’ Giudici, who had initially taken up lodgings at Trent, later moved to the nearby, but more secure, seat of Rovereto, in territory belonging to Venice, where they met with the lawyers, all of top rate importance, whom the Jews of Padua had decided to make available to the defendants (61). Salomone da Piove played a prominent role in the affair, requesting the Pope to appoint an apostolic inquisitor and probably meeting Battista de' Giudici at Padua, on de’ Giudici’s way to Trent (62).

In accordance with de' Giudici, with whom he maintained intense epistolary relations, as well as through another Jew from Piove, belonging to the Cusi family of typographers, having strategically moved, to Rovereto, Salomone provided a safe conduct to a Paduan Jew, a native of Regensburg, and sent him to Innsbruck with the mission of pleading the cause of the Trent defendants still in prison, before Sigismundo, Count of Tyrol, and, if possible, obtaining their release. Salomone Fürstungar, his agent on this delicate mission, was an unscrupulous intriguer who camouflaged himself by dressing, not as a Jew, but "in the German-style, with a short overcoat and a cap on his head", returned from Tyrol disappointed and empty-handed. His bitter failure was also an indication of the failure of the efforts of all the German-origin Jewish communities from the Veneto region to avoid the tragic consequences of the Trent affair for the defendants who were still alive (63).Salomone da Piove is said to have died shortly afterwards (64).

The leadership of this conspicuous group, committed, as always, to avoiding the political and financial effects and repercussions of the Trent trials on their Jewish brethren, thus passed into the hands of Manno di Aberlino (Mandele ben Abrahim) of Vincenza, maximum exponent of the influential Ashkenazim community of Pavia (65). A prestigious banker with vast financial resources, he had been appointed collector ofJewish taxes to the Lombard communities by the Duke of Milan in 1469. Manno was related to Salomone da Piove, whose first-born son Marcuccio had married one of his brother Angelo’s daughters (66). Manno was to meet Salomone da Piove at fairly frequent intervals at Venice, where he had more or less officially opened a money lending shop, of secondary importance compared to the great bank at Padua but still of strategic importance (67).

When Salomone Fürstungar, just recovering from the setback at Innsbruck, thirsting for revenge or just to reshuffle the cards, took to considering murdering the captain of the guards of the podestà of Trent

p. 34]

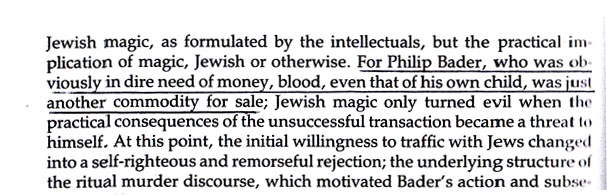

[IMAGE]

[Letter in Hebrew sent by the banker Manno (Mandele) of Pavia to the physician Omobono Bonim of Venice, March 1476 (State Archive ofTrent, Archivio Principesco Vescovile, S.L., 69, 68).] and even bishop Hinderbach himself, hiring an assassin for the task, a person above suspicion, a priest named Paolo da Novara, the industrious Manno offered to finance the bold initiative, without regard to cost (68). Manno asked the priest, Paolo da Novara, who was probably contacted through his brother Bartolomeo, a druggist at Piove di Sacco (69), to poison the persons responsible for the Trent trial and to obtain the arsenic required to do so from the Venetian physician Omobono (Bunim), owner of the "della Vecchia" pharmacy at San Cassian, who is also believed to have issued instructions on how to use the arsenic. As a reward, Paolo was to receive four hundred ducats, half of it immediately, and the other two hundred to be withdrawn over the counter a Manno’s bank at Venice (70). But the conspiracy, the most prominent members of which were all Jews from Pavia, Padua, Novara, Soncino, Parma, Piacenza, Modena, Brescia, Bassano, Rovereto, Riva and Venice, failed miserably, with the arrest and confession of the fanciful and avaricious priest (71).--

p. 35]

CHAPTER TWO

SALAMONCINO DA PIOVE DI SACCO, PREDATORY FINANCIER

Salamoncino da Piove had four sons and a daughter. His family, in addition to managing the ("al Volto dei Negri") lending banks of Piove diSacco and Padua, had major joint interests in other banks operating in Verona, Ferrara, Montegnara, Soave, Monselice, Cittadela, Bassano and Badia Polesine and was active in the textiles and precious stone trade. A secret and elite clientele, ranging from the Sforza at Milan to the Soranzo of Venice (1), came to them for huge sums. Marcuccio, Salomone's first-born son, when not operating in Piove si Sacco and Padua(2), supported by his brothers, stayed at Venice to assist his father in the company set up with David Mavrogonato, and to take over their functions when they accompanied the merchant from Candia in his maritime missions, which were conducted more or less secretly. He was in the City of the Lagoons in the autumn of 1466, as well as in the first half of the following year; thus, he was there in 1468, at the beginning of 1469, during the imperial visit of Friedrich III, and in 1473.

While Salomone was considered a bold and nonchalant businessman, his first-born, Marcuccio, and above all his other son, Salamoncino, darkened his reputation, at least in this respect. Marcuccio was famous to all for his overbearing boastfulness. It was said that, in that of Padua, he used to brag of his strength, real or presumed, with resounding threats: "There is no Christian who would have had the temerity totouch me with one finger, and would not have gotten a good hiding from a couple of well-armed ruffians" (3).Marcuccio, who lived at Padua "facing the Parenzo or il Volto dei Negri" at least until the end of the winter of 1473, made his appearance as an officially approved money lender at Montagnana in 1475. He was still to be found in that financial center at the beginning of the summer of 1494, when Bernardino da Feltre arrived there to preach. On that occasion, Marcuccio did not hesitate to strut about on the piazza with a defiant air

p. 36]

where the violent and fiery Friar da Feltre was expected to preach. As a result, Marcuccio was soon recognized by a Christian who insulted him, and the whole affair terminated in a sensational brawl, with a mutual exchange of fisticuffs, at the culmination of which the infuriated Marcuccio unsheathed his dagger threateningly. It is not surprising that he was to find himself imprisoned in the prisons of the Republic with relative frequency (4).

Marcuccio could nevertheless still count on the influential protection of the city of Venice, which protection he had inherited, together with the privileges obtained by his father, Salomone da Piove. In April 1480, the Council of Ten declared him a fidelis noster civis [loyal citizen] of Venice, under the terms of a law approved by the Serenissima at the end of 1463 on the protection of Jewish money lenders. We know that his father chose to live in Venice during this same period, and it is not difficult to believe that this law was in some way the product of some self-interested initiative (5).

But it was Salamoncino, his brother, who maintained uncontested primacy in this poorly regulated financial sector, where transactions took place with the underworld and the law was only obeyed in those rare cases in which its defenders refused large bribes. Salamoncino took over the management of the bank at Pivoe di Sacco after 1464, when his father took up a more or less stable residence at Venice for the purpose of looking after Mavrogonato’s interests, although -- as we shall see -- he seems to have taken up provisional residence at Verona in the years 1470-1480 (6). In 1474, the Duke of Milan ordered an inquiry of Salamoncino and his suspected accomplices, all accused of illegal purchasing and selling pearls, despite the legal provisions prohibiting Jews from engaging in this trade (7).

Salamoncino had already experienced serious legal problems. In 1472, two common criminals, Giovanni Antonio da Milano and Abbondio da Como, were arrested in Venice under the accusation of importing large quantities of counterfeit silver coin from Ferrara and selling it in Venice, earning large profits (8). This fraudulent trade was operated through a front operation, a butcher shop owned by a certain Nicola Fugazzone, "butcher at Venice", at San Cassian, and a Jewish intermediary, Zaccaria di Isacco, who had his provisional residence in Venice, and was responsible to Salamoncino, money lender at Piove di Sacco (9). The police authorities succeeded in laying their hands on all members of the gang, and they were tried before the judges of the Municipal Avogaria of Venice on 29 May 1472.

p. 37]