Excerpt translated from Italian by C. Porter; comments by C. Porter; emphasis added.

From "The Crematory Ovens of Auschwitz-Birkenau" by Carlo Mattogno and Franco Deana

Excerpt translated from Italian by C. Porter; comments by C. Porter; emphasis added.

390,000 men met in battle at Sedan on 1 September 1870. The tens of thousands of dead soldiers

[COMMENT: Fewer than 6,000 men were killed at Sedan: about 3,000 French and 2,230 Germans.]

were hastily buried in mass graves. This aroused the legitimate apprehensions of neighbouring Belgium, so that the following year, to deal with the situation which was getting worse with the approach of the spring heat, a “Committee for Battlefield Disinfection” was formed at Brussels, presided over by Prince Ortloff, Russian ambassador to Belgium. Two members of this committee, Dr. Lante, a military physician, and [Dr.?] Créteur, a chemist, both Belgians, visited Sedan at the beginning of March [1871]. After an inspection of the battlefield, Créteur proposed burning the bodies with tar [!] and crude petroleum [!] in the very pits in which they lay [!]. The proposal was accepted by the Committee and implemented. The operations, initiated during the second half of March 1871 [COMMENT: NOTE THIS DATE], were described by Créteur himself:

“I had the earth removed which covered the pit down to the layer of fetid earth which was in contact with the bodies, sprinkled this layer with carbolic acid and then had the bodies completely uncovered.

“I sprinkled the uncovered bodies with calcium chloride and had tar poured over them, in such a way that it penetrated all the layers of bodies. I then set fire to the tar with straw soaked in crude petroleum. The fire very quickly ignited the clothes and fleshy parts, and the heat became so intense that it was impossible to get any closer than 4 or 5 metres away. The intensity of the heat obtained was so great that, for the more completely filled pits, only 50-60 minutes were required, and the excavated earth dried completely and was cleansed of the debris of cadavers.”

[1] Source: H. Fröhlich , Zur Gesundheitspflege auf den Schlachtfeldern, p. 101. In this regard, see also: Fernard Marmier, Cremation des cadavres à la suite des grandes batailles et des epidemies. Thèse pour le doctorate en médecine. Paris 1876, pp 33-34; Charles Durous, Essai sur l’assainissement des champs de bataille. Thèse pour le doctorat en médecine. Paris 1878, pp. 13-14.

After burning, the contents of the pit was reduced to three quarters of the initial volume; only the bones remained, enveloped in a resinous layer which protected them from exterior atmospheric agents. The quantity of tar used depended on the number of bodies to be burned, 2 tons for 30-40 bodies.

[2] Source: Fröhlich, p. 102

Créteur claimed that he had, between 10 March and 20 May 1871, with the assistance of 27 men, reclaimed 3,213 mass graves with the bodies of soldiers and animal carcasses, at least three quarters of them using the procedure described above. The total consumption of tar was 304 tons.

Créteur’s report was nevertheless placed in doubt by the other members of the Committee, in particular by Dr. Lante, either regarding the quantity of tar used per grave, or regarding the number of mass graves reclaimed, or, finally, with regards to the results obtained .

In his report, Dr. Lante objected that a mass grave with 10 men required 2 tons of tar, and that, with the 384 tons consumed, Créteur, based on his own statements – the consumption of 2 or 5-6 tons per grave – could not in any case have reclaimed 3,213 mass graves.

[3] Source: Fröhlich, p. 103.

[COMMENT BY C. PORTER: 384 tons divided by 2 = 192 graves x 10 bodies per grave = 1,920 bodies maximum. In other words Créteur, according to his own figures, cannot actually have cremated more than 2,000 bodies, if that.]

Créteur’s statements were also found to be hardly credible in regards to the results actually obtained. One authoritative contemporary, the physician of the [Prussian] Reichs Headquarters, Dr. Fröhlich, observed:

“That the so-called burning process proved satisfactory can in no way be asserted with certainty, as claimed by the chemist Créteur. The procedure did not in fact result in combustion in the chemical sense, but only charring; nevertheless, even this, which in itself would have been sufficient for purposes of hygiene, was not obtained to the extent necessary to render the cadavers harmless. In fact, in particular, the hydrocarbons in the tar certainly burnt off before the soft parts of the bodies caught fire. In consequence, the oxygen in the air was exhausted so completely that only a small proportion remained available to char the bodies; even this small proportion of oxygen only had the direct effect of charring the bodies if the body parts had already lost a great deal of their aqueous content. It was thus found that only the uppermost layers of the bodies were charred, while the contents in the lower layers, where the oxygen could not penetrate (this would be especially true in mass graves), were not charred at all, or were charred only partially, while the flesh in the lower layers, in the presence of a more efficient calorific effect, was [merely] roasted”.

[4] Source: Fröhlich, pp. 109-110.

Another notable source, Dr. Wilhelm Roth, author of a major treatise on standards of military hygiene, in turn raised serious doubts as to the results of mass cremation, “particularly when carried out in a pit”, based on the completely contradictory opinions of the Metz Commission.

Two armies of nearly 500,000 men had met in battle at Metz, between 14 August and 27 October 1870. 14,000 men died in the Canton Gorze as a result of the battle of 16 August, nearly 30,000 men on all the battlefields [around Metz] put together. The rotting bodies contaminated the air and ground waters, for which reason a Committee was formed on 16 February 1871, consisting of the physician of the [French?] High Command, Dr. D’Arrest, and the physician of the [Prussian? French?] Head Quarters, to carry out the job of disinfection.

[5] Source: Fröhlich, pp. 46-47. Dr. Wilhelm Roth, Desinfectionsarbeiten auf Schlachtfeldern, in: Roth und Lex, Handbuch der Militärgesundsheitspflege, 1872, p. 549.

This committee carried out experimental cremations which were carefully described in the report by the two above mentioned physicians. The experiments were performed only in rather small pits, using dead horses only, on the grounds of respect for the dead. For this purpose, the bodies selected were those which could no longer remain where they were, but whose transport to a more suitable location presented particular difficulty. The procedure employed was as follows:

“The bodies [of the horses] were therefore exposed, after having been only summarily buried, using the precautionary measures mentioned in the description of the exhumation, but with the difference that, instead of calcium chloride, we used tar, which was poured as abundantly as possible on the exposed body parts. Bodies covered with tar, removed from their original location, which were usually a bit moist, were placed on a sort of hearth consisting of large heavy stones. They were then covered all over by dry branches and straw, sprinkled again with tar as abundantly as possible, then sprinkled with petroleum and then set alight. High flames immediately developed, generating dense columns of black smoke, pitch and such intense heat, that one would have thought that the bodies, enveloped entirely by flames, would have been burnt in a short time. But after only half an hour, the fire diminished so greatly that it was necessary to refuel it continually, pouring on more tar and petroleum to prevent it from going out completely. After approximately two hours, the heads, necks and tibiae of the animals were badly burnt, but the great masses of flesh of the trunks were only roasted, covered by a layer of pitch which no doubt prevented the in-depth penetration of the heat. For this reason, many profound incisions were made in the flesh, i.e., the muscles of the hind quarters, after which the abdominal cavities were opened; the viscera -- which had barely gotten hot -- were extracted, and dry branches and straw stuffed inside, in their place; the flesh was then once again sprinkled with tar and petroleum, as abundantly and carefully as possible, and set alight. Again, enormous sooty flames and tremendous heat were generated, but once again, after two hours, only slight progress was observed in the destruction. After five hours of work, carried out on several bodies simultaneously, and repeated at other locations, satisfactory results -- i.e., the charring of the flesh of the bodies – were found impossible to obtain; the only thing that could be done at this point was to load the still conspicuous fleshy parts onto sleds and transport them to high ground.”

It was therefore decided to abandon this system of disinfection. In view of these experiences, Dr. Roth concluded:

“Therefore, as the most probable result of Créteur’s procedure, it can be admitted that only the superficial layer of the bodies were charred; it is hard to believe that there was any alteration at all on the interior of the graves, entire cadavers perhaps remaining intact.”

[6] Source: Dr. Wilhelm Roth, Desinfectionsarbeiten auf Schlachtfeldern, op. cit., pp. 556-557.

Créteur had, however, reawakened interest in the idea, and the problem of mass cremation in consequence of possible military clashes (notwithstanding the opposition of some military physicians)

[7] Source: Prof. Dr. Schultz-Schultzenstein, Luftpestung im Felde und deren Verhütung, in “Allgemeine Militarärtzliche Zeitung:, no. 46, 1870, pp. 364-367. Other military physicians were enthusiastic supporters of cremation. Cfr. Dr. Lanyi, “Über die Verbrennung der Leichen am Schlachtfelde", in: “Allgemeine Militarärtzliche Zeitung”, 12 April 1874, pp. 91-95."

and epidemics, was studied by cremation specialists.

--

End of excerpt by Carlo Mattogno

----

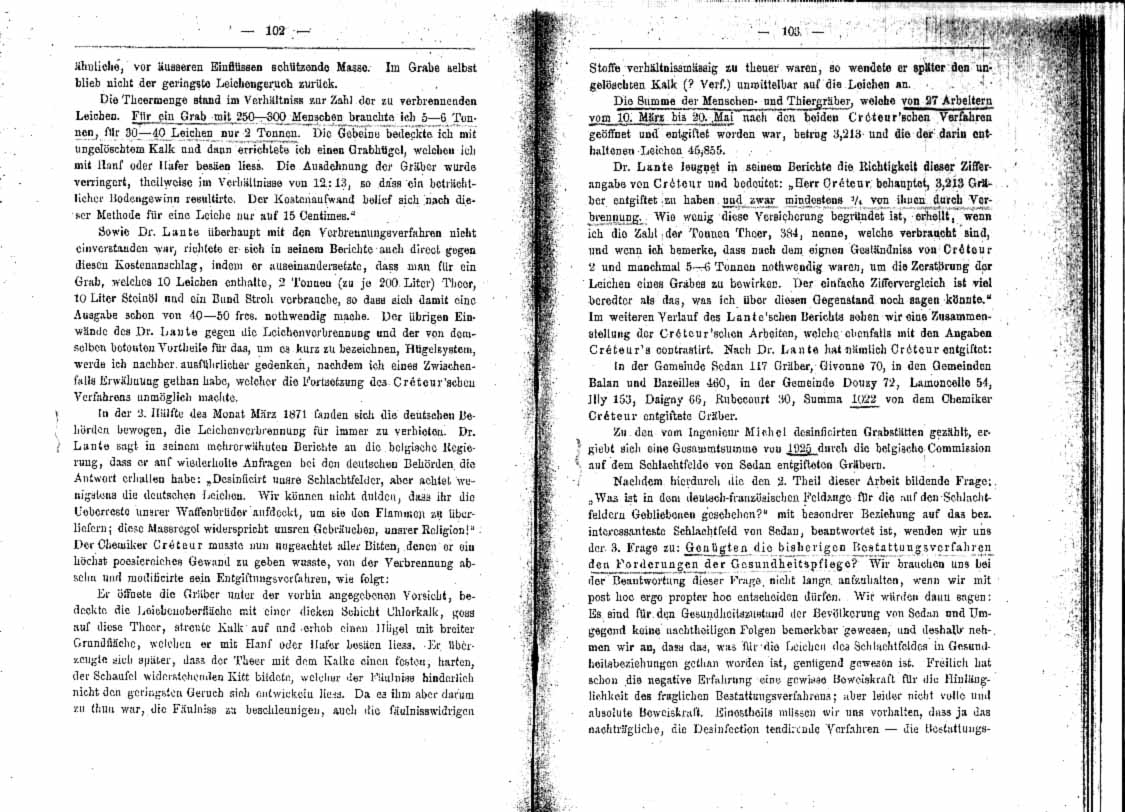

COMMENTS BY C. PORTER: According to the documentary material sent to me by Carlo Mattogno, i.e., excerpts from the article by Fröhlich quoted above, the Prussians prohibited all further battlefield cremation in the second half of March 1871 (op. cit., p. 102, see graphic below, about 2/3 of the way down the left-hand page).. They did apparently permit Créteur to enter France and perform some experiments on French bodies only (reading between the lines), but appear to have been rather, or even entirely, ignorant of what Créteur actually did, since no German bodies were involved.

It is my belief that Créteur was a financial swindler who set up a "Committee for Battlefield Disinfestation" (today it would be "Tsunami Relief" or something similar); enlisted the aid of a few prestigious suckers, including the Russian Ambassador and at least one other doctor, to appear on the letterhead of his organisation (just as swindlers always do); diverted the money to other purposes; and then wrote a report full of lies to justify the disappearance of the money. This explains why Dr. Lante, a member of Créteur's own committee, was entirely ignorant of what Créteur actually did in France, and published a report stating he didn't believe it, even though he had earlier claimed to have entered France with him! This is typical of many financial swindles, in which the directors fall out with each other and claim they weren't aware of the activities of the other directors (for example, the Panama Canal swindle in the 1880s, in which the builder of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps, and Gustave Eiffel, builder of the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty, were enlisted to serve as "useful idiots" while the other directors bribed French politicians and newspaper reporters to lie about the disappearance of the money, resulting in a crash in which 800,000 investors lost their dough). Dr. Fröhlich of the Prussian Army apparently didn't believe Créteur either; after which Dr. Roth of the Prussian Army then conducted experiments proving that Créteur was a liar, and that cremation in the manner described is simply impossible.

Carlo Mattogno believes that Créteur did enter France and performed some cremation work; the question is how much. I am not sure I believe any of it, for the following reasons:

a) I have travelled the regions of rural France where much of this fighting took place: anywhere there was the slightest military activity, you will find beautifully carved, very expensive, war memorials, built by the Prussians, even in relatively remote fields and forests where few people will see them. A few hundred yards away, you will find a French monument on the same spot. Some of these monuments are very small (although bigger than a man); yet they are some of the most beautiful war memorials I have ever seen. In some regions, there is a monument every few kilometers. It is obvious that both sides respected their war dead and did not intend to allow somebody else, an outsider, to treat them like garbage.

b) Battlefield cremation to prevent disease and the pollution of ground waters is plausible using wood for fuel; it is not plausible using petroleum and tar. A focus of infection will die out eventually, once the bodies have completely decomposed; but if your ground waters and farm land are polluted with tar, coal tar, muriatic acid, carbolic acid, they will remain polluted a great deal longer, if not forever.

c) If the pollution of ground water was such a problem at Sedan, where fewer than 6,000 men were killed (Mattogno has made a mistake here), then what the hell did they do after the battle of Gettysburg, only 8 years earlier, where 52,000 men were killed?

d) By comparison, the Confederate states were defeated, were indigent, and had no legal rights after the American War of Southern Secession (probably the most correct and neutral name for the "American Civil War".). Yet large sums were spent after the war to recover Confederate dead and transfer them to Confederate cemeteries. This is not something which can improvised. A farmer who finds a body on his land has to know which agency to contact to have it removed so he can resume farming; farmland must presumably be condemned or purchased to serve as cemeteries; each belligerent must have access to the territory of the other belligerent after the war. Huge sums were also spent by the German authorities after 1919, even though Germany was totally bankrupt. These matters are usually worked out in detail either in the peace treaty itself or in post-war treaties. All the Geneva Conventions signed since the 1880s or so prohibit any desecration of war dead, although the treaty in effect in 1870-71 does not mention the matter. Even so, there was no desecration of the dead during or after the 1861-65 American conflict, which ended only 6 years earlier, in which 615,000 men were killed. The bodies were simply buried and recovered at a later time.

d) No one, not even the Prussians who were in charge, seems to know just what Créteur actually did in France in 1871. Nearly all regular military operations in the War of 1870-71 ceased after the French defeat at Sedan on 1 September 1870, but the French continued the war through irregular tactics (guerrilla warfare, using so-called "franc-tireurs", recruited from patriotic rifle clubs, and shot upon capture by the Prussians), until signature of the Armistice on January 28, 1871. We may safely presume that any further guerrilla activity would have been in violation of the terms of the Armistice, which would have entitled the Prussians to denounce the Armistice and recommence hostilities; and that therefore the Prussians were watching everything going in France on with an eagle eye. Yet no one seems to know exactly what Créteur actually did during this period! The Treaty of Frankfurt, which actually ended the war, followed by Prussian withdrawal, was not signed until May 10, 1871. During this period, the Prussians were in total control of Northeastern France; France was an occupied country, with no rights, except as guaranteed under the Armistice and under military law. Yet no one knows what Créteur actually did during this period! I don't believe it. I believe that Créteur was a financial swindler and a liar. Obviously there cannot have been any stock and bond sales, as in the Panama Canal Affair, because battlefield disinfection cannot have been expected to yield a profit. My belief is that Créteur raised funds by subscription, as a charitable and humanitarian venture, from philanthropists, charities and/or from public funds in Belgium and/or elsewhere.

e) According to the source material (i.e., the Fröhlich report, page 102), the Prussians had already prohibited all further cremation at the time when Créteur claimed to have performed most of his cremation activities.

It would be interesting to know whether Créteur was involved in any other swindles or shady deals, what finally happened to him, and what his full real name was. Nobody seems to know his first name, or even what his qualifications were, or anything else about him. He is simply referred to as "Créteur", a "chemist".

[I have seen Créteur referred to as a "Colonel", once; whether this is true or not, or just another mistake via the Nizkoprophagists, appears to be anybody's guess. Fröhlich is obviously describing his own observations of Créteur's wizardry, so how many bodies were involved? 10? 20? 100?]

CONCLUSION: Putting it very crudely and approximately, really, we have only Créteur's word for it that he did anything in France at all (he appears to have done something, but very little, perhaps just as a pretense). If he lied about 90% of his activities, how do we know that he told the truth about anything at all?

The Panamal Canal Affair involved many Jews

(such as Baron Reinach and Cornelius Herz) in the background; it would be interesting to know the full truth about this affair.

At any rate, cremation in pits is impossible, at Auschwitz, Sedan, or anywhere else.

CARLOS W. PORTER

NOV 20, 2005

See also: John C. Zimmermann, HOLOCAUST DENIAL, chapter 10, for his take on this rather silly story.

On the Panama Canal scandal and anti-semitism, see http://www.historyhome.co.uk/europe/3rd-rep.htm#panama

Quote, left-hand column, about 2/3 of the way down: "During the 2nd half of the month of March 1871, the German authorities found themselves compelled to prohibit all further cremations". ["In der 2nd Hälfte des Monat März 1871 fanden sich die deutsche Behörden bewogen, die Leichenverbrennung für immer zu verbieten."]

MANY THANKS TO CARLO MATTOGNO FOR HIS KIND ASSISTANCE